Diary Entry

The vast city of Saigon is more than impressive. However, this city and this part of the country fought on the American side against the victorious communist North of Vietnam. All of Vietnam was a battlefield at the time, and its inhabitants were victims, often unwitting soldiers. Outside the city, there is another museum that depicts the incredible conditions during the Vietnam War: the Củ Chi Tunnels.

It takes us about an hour to get to Củ Chi, and the earlier in the morning, the better the chance of having less activity on the site.

We quickly raid what we find at the breakfast buffet, because unfortunately, it doesn’t open until 7:30. In the meantime, Ian has arranged a minibus for us and is collecting our passports so we can get our visas for Cambodia. He speaks with a raspy voice and seems to have a terrible hangover. He also stays behind at the hotel.

What I see of the surroundings as soon as we leave the city are simple houses, huts, and endless rubber plantations. The simple paved roads, which barely have room for one vehicle, barely deter the driver from driving below 70 km/h. In the driver’s defense, I have to say that I haven’t seen a single speed limit sign anywhere. I haven’t seen one in the entire country so far. We drive into a large square with a few office shacks.

There, we get tickets and sit in the TV room, where a propaganda film is shown depicting the deeds of women and war heroes who endured pain, death, and deprivation, even under the most primitive conditions, to defend the country. It shows the Ho Chi Minh Trail, the Viet Cong’s extensive supply route that led from North Vietnam through Laos and Cambodia to the south, supplying the troops there with weapons and food, enabling the conquest of Saigon and thus South Vietnam.

The Vietnam War

The origins of the war lie in the colonial era, when Vietnam was part of French Indochina. After World War II, the communist Viet Minh resistance movement under Ho Chi Minh sought independence and defeated French troops at the Battle of Dien Bien Phu in 1954. As a result, Vietnam was temporarily divided at the Geneva Conference: North Vietnam became communist under Ho Chi Minh, while South Vietnam became pro-Western under Ngo Dinh Diem.

From 1955 onward, the conflict escalated when the United States began providing military and financial support to South Vietnam to prevent the spread of communism. The Viet Cong, a communist guerrilla movement in the South, intensified its attacks. In 1964, the Tonkin incident led to the United States’ official participation in the war, sending up to 500,000 troops to Vietnam in the following years.

The war reached its peak between 1965 and 1968. The United States used massive air strikes, napalm, and the defoliant Agent Orange.

The Tet Offensive in 1968, a large-scale offensive by North Vietnam, shook the US public’s confidence in victory and marked a political turning point.

Starting in 1969, the so-called “Vietnamization” began, with the US gradually withdrawing and South Vietnam assuming responsibility for the war. A ceasefire was agreed in 1973, and the last US combat troops left the country. Nevertheless, North Vietnam continued its advance and captured Saigon in 1975, ending the war and reunifying Vietnam under communist rule.

The Vietnam War claimed over three million lives, left profound social and ecological scars, and led to a fundamental shift in US foreign policy. Vietnam was officially declared the Socialist Republic of Vietnam in 1976.

The Viet Cong organized their guerrilla war against the Americans from the Cu Chi Tunnels. The tunnel system stretched for kilometers. It contained all the facilities, such as kitchens, dormitories, armories, even bars, schools, and temples. The tunnels were protected by booby traps, which unwitting American GIs would trigger if they found and explored one of the tiny, hidden entrances.

The guide explains everything again using a map and a model cross-section of tunnels. Then he leads us out and across the road into the forest, where we are accompanied by a soldier. The forest consists of young trees, bamboo, and a type of aspen.

The guide explains to us that all the craters were caused by bombings, because the Americans bombed Cu Chi with everything they had: cluster bombs, which cause numerous small explosions, 500-kilogram bombs, which create deep craters, and Agent Orange bombs, which defoliate plants and, after a while, completely destroy them, as well as all living things that come into contact with them. And this still happens today, through contaminated groundwater. Napalm bombs ultimately burned everything that hadn’t been rendered harmless by everything else that came before. In total, more bombs fell on Vietnam than on all European countries combined during World War II.

More bombs fell on Vietnam than on all European countries during World War II!

The so-called Agent Orange chemical is still found in the soil and repeatedly causes horrific deformities in new generations. Eucalyptus trees are now being planted to counteract this, as they are quite effective at extracting this substance from the soil.

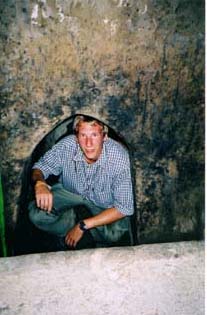

We pause, and almost out of nowhere, our guide opens a small trapdoor in the floor, measuring just 20 by 30 centimeters. This is one of the entrances to the tunnels.

Jane and Becks try their luck and squeeze in. Then I try it too, but I’m quite a bit bigger than them, and it takes some acrobatics before I too disappear into the hole. But I can’t make myself small enough to follow a passage. At least, unlike the girls, I can get out of the hole under my own power.

Again and again we see trenches that provided cover for the Viet Cong and small entrances into them.

Finally, in the forest, a hut has been set up, displaying all the different traps an American GI could fall into. The so-called booby traps were holes in the ground, the simplest with sharpened bamboo poles at the bottom. More complex traps were wheels with spikes that you step on first, which rotate on their axis, and then stab you in the head again after you’ve fallen to the bottom of the trap. Entire gear systems made of spikes torture their victims, because the goal isn’t to kill them, but to inflict such severe wounds or cripples that they are defenseless in war or die from infection.

There really are no limits to people’s sick imaginations when it comes to inventing ways to kill other people. Concerned, I ask our guide if they’re sure all of these traps have actually been found.

We pass an old, weathered tank wreck and hear gunshots in the distance. There’s a shooting range here where you can shoot weapons of war. A bullet costs a dollar. I want to experience it, so I shoot an M-16, the “tried and tested” American machine gun. Luckily, there are ear protectors, because the shots are extremely loud. Then I can also test out an AK-47 “Kalashnikov.” The recoil almost knocks me over.

In a hut, a few electric-powered puppets suggest the Viet Cong (which is simply the term for “Communist Vietnamese”) making grenades and mines by recycling used shell casings or unexploded bombs. To destroy tanks, men and women used to commit suicide by throwing themselves at the vehicles with adhesive mines, as they usually couldn’t escape the explosion in time. They are celebrated as national heroes.

Further into the forest, there are cave entrances, and the guide invites us to crawl along for a few hundred meters. The boys and Jane give it a try. After climbing a few meters down the steps, we find a small passage that leads further. It’s no more than a meter wide and high, and only lit at first, then the light goes out. The air is humid and stuffy, threatening to take your breath away. You can only crawl slowly on your knees along the passage, feeling for its direction with your hands. A panic I don’t recognize rises within me, the first claustrophobic feeling of my life. I try to suppress the panic. Behind me, everyone seems to have turned around; in any case, I can no longer hear anything from that direction. In front of me, everyone seems to be far away. The ground is soft and damp. And everything around is pitch black. My elbows and my head repeatedly confirm how narrow it is. My breath is now racing, and I want to get out of here as quickly as possible.

It’s almost midday now and oppressively hot. Sweat is running down my forehead as if I were taking a shower. We sit under a roof, and the guide hands out chestnut-flavored tea and a sticky, dry vegetable to go with it. Now the mosquitoes are really starting to get annoying; they swarm us by the dozen. I left my mosquito repellent at the hotel, but Becks helps me out. The mosquitoes aren’t impressed in the slightest, though, and my sweat washes the protection right off. A sticky layer of water covers my arms, and water drips evenly off my chin. I’ve never experienced anything like this before; it doesn’t seem that hot at all; it’s just incredibly humid.

I take the first branching passage and find a glimmer of light, which I quickly crawl towards. At the surface, I find my friends again. Everyone is there, except for Glen. He also emerges from the hole after a few minutes and also complains that everyone is gone.

Finally, we see a few small, hidden bamboo tubes that ventilate the corridors, and a kind of chimney in the floor through which the smoke from the kitchens discreetly escapes, before we return to the bus past a few souvenir shops. There, my sweating subsides. We head back past the rubber plantations and into Ho Chi Minh City.