Diary Entry

We leave beautiful Hoi An and head for Đà Nẵng, where we take a small plane to Ho Chi Minh City – the former, promising Saigon. The town is large, with the usual terraced houses with balconies and flat roofs lining the beach. Unfortunately, the buildings that only have front-facing windows are located all alone somewhere in the countryside. The reason is the high population density, which only allocates a certain size of living space (approximately three by fifteen meters). Nobody in the countryside adheres to this rule; only occasionally do you see such houses here. But in the city, it’s mandatory, even if you own a house away from the predominantly inhabited area.

The city is very large, but we only need to get to the airport, which is sleepy and far from the residential area. It’s now small—there’s no sign or trace of what Da Nang Airport was 30 years ago, the busiest airport in the world, as an American air base.

In a few minutes I have checked in my luggage and am strolling through the streets for a while.

I go through security a little early, as I’ve had bad experiences before. But nothing happens; I get through security faster than my luggage gets onto the plane, so I can leisurely browse the souvenir shops in the deserted lounge and watch some music on the big screen. From the lounge, our group is taken by bus 50 meters to the plane. This time, it’s a small Airbus. After a call from a friend in Saigon, expedition leader Ian tells us that there just happens to be an international match between Vietnam and their arch-rival Thailand taking place there today. We’re all immediately excited to see the game.

Really? An international football match?

The plane takes about an hour and we have to hurry from the airport to catch the start of the game.

The taxi, however, takes some time to find the hotel. Ian warns us about the hotel, as there are always some misunderstandings, whether it’s that there are no towels, or that everything in new rooms is fine except for the fact that there are no blankets. At first glance, however, our rooms seem fine, so we give our passports to the receptionist and order two taxis. However, the stadium is on the other side of the city, which, with almost eight million inhabitants, is twice the size of Hanoi.

The outskirts are dreary, with miles of simple houses, the same traffic, and no trees.

We finally reach the stadium; it’s been ten minutes since kickoff. We buy our tickets and look for our seats. Officials have to shoo a few people away from our seats before we can sit down; we shoo away a few slower-witted people ourselves. Of course, the shady spots in the stands have been reserved for rich tourists. The game is funny. The Thais are clearly superior, but about every five minutes a player falls to the ground and the paramedics arrive. The spectacle becomes so absurd that we end up shouting after the paramedics and cheering them on. Even a goalkeeper gets injured. After the match, there’s another game, Laos versus Malaysia, which we watch until halftime, until we get bored and get a taxi back to the hotel.

Ho Chi Minh City is twice the size of the capital Hanoi!

Ho Chi Minh City – the former Saigon

The history of Ho Chi Minh City

Ho Chi Minh City, formerly known as Saigon, is located in southern Vietnam and is now the country’s largest city. Originally inhabited by Khmer peoples, the region was taken over by Vietnamese settlers in the 17th century. Under French colonial rule from the 19th century onward, Saigon developed into an important administrative and commercial center and was often called the “Paris of the East.”

One theory suggests that the city’s name, “Sài Gòn,” could come from the Vietnamese “Sài” (a tree or wood) and “Gòn” (kapok tree), meaning “place of kapok trees.” Other theories suggest the name could be Khmer or Chinese.

After the end of French colonial rule and the division of Vietnam, Saigon became the capital of South Vietnam.

The city was a pivotal theater during the Vietnam War. On April 30, 1975, Saigon fell to communist North Vietnamese troops, marking the end of the war and the reunification of the country.

Why is Saigon now called Ho Chi Minh City?

After the reunification of Vietnam, the city was officially renamed Ho Chi Minh City in honor of Ho Chi Minh, the revolutionary leader and president of North Vietnam, who played a key role in the country’s independence and reunification. The name change symbolizes the political transition and the new era under communist rule.

Despite its official name, “Saigon” continues to be widely used in everyday life, especially in cultural and historical contexts, and by both locals and tourists.

It’s already evening, and Ian knows a great restaurant for grilled specialties. We, except for Jenna and Nicki, take two taxis to the restaurant. It’s huge; at first, it looks like a large Oktoberfest beer tent we’ve entered at night, but the Asian waitress and the strange menu suggestions on the wall prove us wrong. There are rats, scorpions, snakes, spiders, pufferfish, sharks, turtles, grasshoppers, and everything else that can crawl or swim.

A waiter leads us through the benches and tables occupied by shouting Australians or boisterous Vietnamese, up a staircase one floor higher, which is the same size as the ground floor but from which you can still see it.

As usual, we order beer and a barbecue, which means we get two large grills on the table, on which we grill beef and pork, along with onions, tomatoes, and all sorts of exotic vegetables. We also get bowls of rice, sauces, and a small bowl in which we can mix everything together and eat it with our chopsticks.

The food is magnificent, especially the garlic-seasoned rice, which tastes fantastic with the sauces and meat. A cake suddenly arrives at the next table, and the Vietnamese people start singing a birthday song. We immediately join in and toast the birthday boy, and we promptly get cake, too.

Out of curiosity, I order a scorpion. It arrives immediately. I’m curious to see what it will look like, whether I’ll be served an indefinable mass or a real whole scorpion. The waiter brings me a plate with a whole black scorpion, garnished with a tomato. My friends are almost taken aback. I take a closer look at the insect, and there’s no doubt it’s real. The creature is light, apparently well-cooked. I break off a pair of claws and taste it. Very crispy, with a slightly bitter aftertaste. My companions grimace and laugh. But they don’t want to try it. I take the scorpion and bite off its head, eating it with its tail and stinger. It won’t fill you up; it tastes different and is definitely worth the experience.

Afterwards, we wander around the bars a bit, originally planning to go to “Apocalypse Now,” a bar almost as famous as the film of the same name, but we end up stopping at an Australian pub. We order another round of beer, and I should mention that the beer bottles usually hold three-quarters of a liter. This is our third of the evening, with more to come. Of course, the bar is run by Vietnamese, but as Glen says, it looks exactly like any pub in Australia. Hanging on the wall are a few boomerangs, stuffed crocodiles, maps, and pictures of Australian football teams. They even offer a local round of Baileys on the house.

Meanwhile, Euen and Kevin are defeating one team after another at billiards. Glen and I are competing against them again, and after knocking all my balls off the table in three rounds, I pot the black ball in the right pocket, but tragically, I also pot the white ball, and the game is lost. Nevertheless, I’ve at least broken the humiliation of the last game in Hue.

After a chat with the barmaid, I play some darts with the others. I join in late and catch up pretty quickly, but I can’t catch Jane in the close duel.

Ian is once again delivering his moralizing sermon as his uncle, who is trying to make a man out of Glen over the course of the trip. Glen is very uptight around the womanizer Ian; Glen had already disappointed him with the “alarm clock” incident in Luang Prabang. Of all people, the womanizer’s nephew was the one who backed down like that. And then he’s so afraid of taking risks, he should take my example. But I’ll refrain from that for now. Glen, however, has sunk into the ground, because the people still in the bar are listening.

Despite Ian’s drunken state, he seems to know where he’s going, and even though he’s staggering, he still speaks almost clearly. I have to say, I think our “leader” is great.

It’s now 1:30 a.m., and we’re on our way to the hotel. Ian says he knows the way, so we’ll skip the taxi. However, he’s completely drunk, which is clearly evident from the way he walks.

We chat a bit more exuberantly about everything under the sun, and luckily I’m still lucid enough, as I haven’t had much to drink this time, to avoid any long encounters or possible outings with shady characters. But that doesn’t happen, and we reach the hotel an hour later.

Ian puts Glen and me back on the waiting list, but it’s a long time before we get our turn. The Scots are disqualified by an agitated billiards supervisor, who watches every game from a seat by the wall and intervenes in case of rule violations, after Euen, following a questionable shot by his opponent, deliberately only taps his ball. The Scots leave the bar under loud protest; the girls have already left for the hotel. Only Ian, Glen, and I, along with a handful of guests, are still in the bar, waiting for our round.

The billiards supervisor is about to drop us, but we manage to persuade him to let us play. The game isn’t going well, the others aren’t particularly good, but Glen and I are lacking the right opportunities.

I manage to catch up a bit for us. Glen wastes two moves with a ball that’s unpottable at one corner. Ian and I argue with him like world champions, telling him to avoid that ball, but he won’t listen and fails a third time with the ball that seems less risky than another one I recommend. Our opponents immediately take advantage and win.

In contrast to the daytime, when traffic is so heavy that it’s almost impossible to cross the street safely, the street is now completely deserted. Pretty, made-up girls stand in front of small, shady bars, trying to lure us into their establishments. We politely decline each time. Ian starts joking with a sort of pimp who starts chatting us up on the street, but I pull Ian along, for which he thanks me. We now stagger down the middle of the street, passing through alleys, pausing at intersections and now-deserted traffic junctions, joking with a few taxi drivers and motorbike drivers who occasionally pass by and chat up us, until finally the streets are deserted again, and at most, a rat crosses our path.

Check out more of my juvenile trip through Indochina!

It’s time to reflect on this major turning point in Vietnam’s young history. The war tore the country apart, and now it has grown back together, but the scars are visible everywhere. I visit the Cu Chi Tunnels outside the city. Afterwards, I devote some time to the War Museum in Ho Chi Minh City.

The museum consists of several areas, photographs, and war relics. The photographs depict crashed planes, final shots of reporters, soldiers in trenches, helicopter squadrons, napalm attacks, running children, faces crippled by Agent Orange, desperate faces, soldiers taken prisoner, executions, and bodies torn apart by grenades. It also displays the divisions that arrived in Vietnam from America, Canada, New Zealand, and Australia, as well as war insignia. Maps depict the Vietnamese and American attacks. The Tet Offensive ultimately ended the war in 1968, and after the capture of Saigon, the Americans withdrew from Vietnam.

Exhibited are jet fighters, anti-aircraft guns, cannons and artillery, tanks and bombs as big as cars, machine guns and mines, as well as pictures of children taken during the war. However, the museum shows how horrific the war was on both sides. It doesn’t take a propaganda stance like some other museums; it not only shows the crimes of this war, but also that war itself is a crime, no matter where it takes place.

The now sadly infamous image of the naked girl running screaming down the street with a few other children while explosions rage in the background is also located here.

As we take in the paintings in the museum, the monsoon returns. After a heavy downpour, the weather settles back into overcast skies and drizzle.

Lady Jane, of course, has her small umbrella with her, but fortunately the rain is holding off as we head for the palace of the last president of South Vietnam. I see on the map that it’s just around the corner. Of course, we take the wrong side and have to walk all the way around the railing. The Scots, annoyed by the rain, simply take off with Brian. Mia is “grumbling” along because she didn’t have lunch.

We ask our way past a few gatehouses until we finally find the main entrance. The palace itself is also a museum, but it’s truly famous for the tank standing in front of the palace. This was the tank that entered the palace grounds, symbolizing North Vietnam’s victory.

Also famous is the scene in which the North Vietnamese general meets the South Vietnamese president for the last time. The latter says, “I am pleased to hand over my office and my country to you,” to which the North Vietnamese replies, “You cannot hand over to me what was never yours.”

We’re disappointed to discover that we have to pay an entrance fee, even though we don’t want to see the museum. But luckily, it’s not that much. The tanks are parked under a few trees, their guns pointing toward the palace.

We take two taxis back to the market, which is quite close to our hotel. I leave my companions here to find the Kodak store again and a bank. Along the street, just like at the market, there are shops selling clothes, fake watches, burned CDs, and souvenirs. I find both my camera shop and a bank.

It’s still raining, and I’m already soaked to the skin. On the way, I run into Becks and Mia again.

Across Saigon’s busiest intersection, a roundabout in front of the Grand Market, I fight my way through the traffic as if in a game of skill, swinging axes and clubs.

I manage to get to the market alive and look around a bit, partly to stroll around, partly to maybe find Jane and Glen again.

The market is nice, with a few large market halls housing the usual wares of clothing, counterfeit CDs, watches, and art.

I find a beautiful silk jacket, decorated with a dragon sewn on the back and a Wheel of Life in the same black as the jacket. Ten dollars seems incredibly good value for money. But since the merchants don’t accept credit cards, I’m already broke.

I immediately bump into Jane and Glen, who were also shopping. We walk a bit through the streets, then we split up again. Jane looks for an internet café, while Glen and I look for the hotel. I desperately need dry clothes.

In the evening, I meet up with Jane, Becks, Mia, and Glen for dinner, and we stroll around for a bit. Along the way, I meet Phung, a scooter driver, with whom I chat for a while until we find a fine French restaurant serving Asian dishes in the French tradition.

In the evening, I actually wanted to go to the Apocalypse Now bar with Glen, but it’s raining so heavily again that we can’t go out on the street.

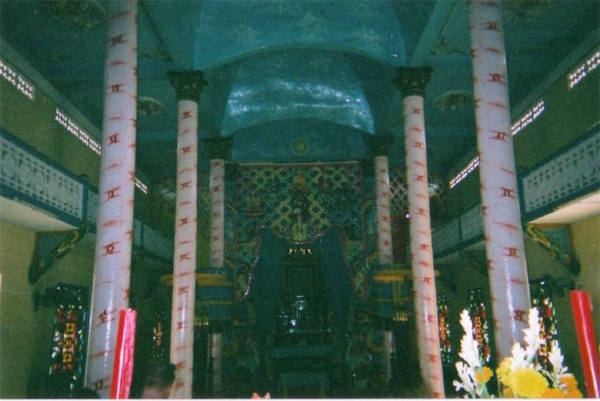

The next morning, we leave Saigon again by minibus and head toward the Mekong Delta, the fertile southern tip of Vietnam. We pass through many villages and rice fields, where residents dry their rice on the street. We stop at a brightly colored church, which, Ian says, belongs to the religion of Qaedaism. This religion combines Christianity with Islam, Buddhism, and Chinese teachings, and venerates Jean d’Arc and Winston Churchill as saints.

The two-towered church is yellow, with a blue roof and colorful facades. Swastikas, symbols of the sun, are emblazoned on an obelisk at the entrance. We are greeted at the entrance by a kind of mullah.

Inside, the church looks more like a mosque, with blue ornamentation on the walls and floor, which also houses prayer cushions. However, there is an apse and an altar. On the altar is the symbol of a large eye in a pyramid, and around it are Jesus, Muhammad, Buddha, and the Chinese god of war. Surrounding it are bowls of incense sticks and fruit.

I donate two hundred dong to the church and sign the visitors’ book as Indiana Jones.

We make another stop for lunch at a roadside restaurant. The restrooms are awful, and the restaurant looks more like a pet shop, with its aquariums, fountains, and cages of frogs, snakes, eels, turtles, and rats.

But I stick to a normal menu of rice and vegetables, while at the table next to us a lively barbecue with rats is taking place.

We cross the Mekong by ferry. While the bus stays in the vehicle area, we sit with the other passengers on a veranda above, overlooking the cars. It’s incredibly loud, as the narrow sides of the small ferry reflect the sound three times as much. On the back seat where I’m sitting, a dried-up gecko is still stuck to the paint.

In the afternoon, we reach Chao Doc, the largest city in the center of the delta, through which most of the shipping traffic from the Mekong to the sea and the traders passes. This city has absolutely nothing touristy about it, and as I wander alone through the market, I’m eyed with respect, like the giant Rubezahl. But everyone is naturally quite friendly, and I chat with several of them again, who are also very pleased that I speak a few words of Vietnamese.

Nevertheless, I must emphasize again that compared to the poor merchants, you seem like a foreign prince, striding through the market with your more or less clean, but more expensive clothes, a gleaming watch, six foot three, and blond hair. The mere fact that I’m in that country makes me incredibly rich; I come from a country beyond people’s imagination, and not just in terms of distance.

They cannot afford to cross the border into Cambodia or Laos.

I meet up with Jane, Becks, Mia, Brian, Glen, and the Scots for dinner at a local restaurant. We eat and drink beer. Euen even constructs a fabulous bottle tower out of five large bottles. Brian chats with a few cyclo riders who want to drive us around the area to discos or places where we can have “fun.” Jane whispers to us to keep an eye on Brian, who, as we know, sometimes fails to get out of tricky situations on his own.

The next day, early in the morning, we loaded a small motorboat with our luggage and ourselves and set off up the Mekong towards Cambodia and Phnom Penh.