Diary Entry

We don’t linger long in the enchanting old mausoleum of the dervishes. We drive back through Shamakhi (Şamaxı), which we’ve already seen, and then take a route into the mountains to visit the village of Lahic. Every book about Azerbaijan and every tourist guide in Baku mentions it. So we have to go there.

Thanks to our car, we can go there on our own. Marshrutkas also travel across the country, connecting the cities. I’ve already experienced these in Georgia and can thankfully do without those hellish vehicles.

At first, the road is harmless and winds peacefully through the gentle hills, over which the clouds hang low.

It is already late afternoon and we need to hurry so that we can reach our overnight accommodation before nightfall.

Beyond a pass at an altitude of 2070 meters, the road suddenly becomes quite treacherous. In one section, it simply disappears without warning due to a landslide and is barely passable. Then I notice that I can see another road on the Google satellite image, one that bypasses this one. Apparently, a new road was simply built elsewhere, but they forgot to mark it here.

Shortly afterwards we reach another section of the road that has collapsed. This time there is no detour and I am glad for the car’s four-wheel drive, which proves invaluable on the difficult track.

Thanks to satellite images and all-wheel drive, the route is no problem.

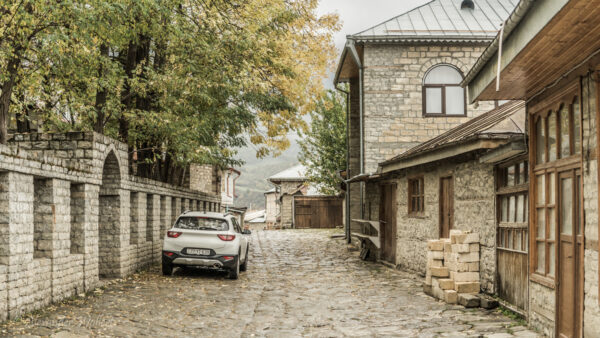

We finally reach Lahıc. The small village lies remotely beside a huge riverbed. For what is supposed to be one of Azerbaijan’s most important tourist attractions, it’s difficult to reach. Darkness falls, and finding our accommodation through the narrow streets becomes challenging. The directions are consistently wrong, the houses aren’t marked from the outside, and the narrow cobblestone streets are barely passable, especially in the rain.

Finally, in the dark and rain, we find the right house and are allowed in.

Using a few words of Russian, we communicate with the old man who looks after the house while his son lives in Baku and rents out the apartment from there.

The man also leads us to a restaurant where they’re still cooking for us. Everything else is closed. We get delicious saj (a mixed grill) and terrible house wine (more like strawberry vinegar). No other restaurants are open, but a family is treating us exclusively. Exclusively, too, is the price. We didn’t even pay that much in Baku.

The next day we explore the town, which is famous for its coppersmiths. I also buy a sheepskin for Leon and a scarf for Sara.

We watch the blacksmiths at work and eat qutab and dolmasi. Even here, it’s not very busy, considering how famous the city is supposed to be.

We are the only tourists, and the souvenir shop owners and blacksmiths are vying for our attention. Not only is the tourist season over, but it’s also Friday.

We suspect that many people in Islamic societies are staying home today.

Perhaps we were simply too early in the morning. A shrewd trader is the early bird who gets us as worms.

He is the only one who invites people into his shop with open doors at nine o’clock in the morning.

Uwe and Chris get to try on some fur hats. As a reward, we actually buy a few things. In return, we get to take some photos with him.

Gradually, the city comes back to life. Every now and then a car rumbles over the cobblestones. Google wanted to send me through here last night. Good thing I didn’t listen to the AI.

A group of men are standing together, watching us suspiciously. A young man lures us into his shop with its brightly colored teas.

The village is beautiful, but very uneventful. Perhaps it’s also due to the bad weather, which is getting us down. We see absolutely nothing of the breathtaking mountain scenery of the Caucasus.

So we continue walking across the slippery cobblestones and become the highlight of the day for a few girls who get to practice some English vocabulary with us on their way to school.

We decide to visit at least one more sight to avoid feeling too culturally jaded. The opportunity presents itself. While we’re admiring a small mosque, a man asks us, “Hammam?” I know from the guidebook that there’s supposed to be an old hammam here. I nod. The man pulls out a key and gestures for us to follow him.

We wind our way through a few alleys until we come to a small staircase leading down. It smells musty. Through a window grate, we can only see rubble.

He explains many things to us in Russian, then in Azerbaijani, none of which we understand. Nevertheless, we are interested in a change of pace.

What we understand is that he wants one manat from each of us if we go through the rotting wooden door, whose lock he has just unlocked. Okay, that’s about 30 cents. He lets us in and leads us through the vault. Then he switches to free-form sign language and pantomime to make us understand what we are seeing.

We can easily imagine this as the changing room, with a hot water basin and a cold one over there. Using our phone lights, we can also see a large basin that now serves as a latrine for the local bats. We’ve seen enough, so we thank the man and give him his money before saying goodbye.

We think we’ve seen enough of Lahic, and the weather forecast isn’t looking any better. A hike with alpine views isn’t really appealing either.

Since we want to go to Sheki (Şəki) next, we’re taking a different road than the one we came on. However, the tourist guides only warn against the road we’re planning to take there, and not the one that already seemed treacherous to us coming from Shamaki.

We ask the locals, using a translation app and a few words of Russian, whether the road is clear, or if we should expect dangers from rain, landslides, avalanches, or damaged roads. But everyone just laughs and indicates that everything is fine. Even the locals here are already using ChatGPT for translation – amazing!