Diary Entry

Our stay in the small imperial city of Hue and our lovely trip into the Vietnamese hinterland are over. We leave the hotel at 8:30 a.m. Glen is so sleepy that he even missed breakfast. We take a minibus south along the coast, stopping at a small seaside town to rest a bit. Afterwards, we wind our way up the serpentine Cloud Mountains that physically and culturally separate North from South Vietnam. The overgrown mountains also form a climatic boundary, from the cooler north to the more humid south.

We make a stop at the Hai Van Pass at an altitude of 1,500 meters. From here, you can see both countries, the valley below, and the sea on both sides. But here, too, tourist-hunting vendors have taken up residence, and now they’re targeting us. We’re greeted with the usual greetings:

„Hello! Where are you from? Would you like to buy something?? Excuse me, Sir, Sir……! Madame, Madame!“

When they address Euen as “Miss,” he gets really angry. They’re the usual veiled saleswomen selling jewelry, fabrics, or food. I escape the hustle and bustle and climb a little way up the mountain through the bushes until I reach an old bunker. This pass has always been an important strategic position for every power, so medieval fortifications still rise out of the rock here alongside new concrete bunkers. From the roof of a pillbox, I have an even better view of the busy pass and the surrounding area, the mountains and the sea. I wander around a bit longer, pass an altar where a horse is grazing, and find my way back.

We pass plantations and fish farms, with bays and islands stretching along the entire coast. Around midday, we reach Hoi An. This small town, with a population of about 30,000, is famous for its artisans, painters, potters, and especially tailors. Ian shows us a bit of the town after we have a quick lunch in a charming little restaurant.

Hoi An is truly enchanting. It has many small streets and, of course, the usual market selling food, fabrics, sunglasses, watches, and art objects. Officially, the export of all Buddhas from the country is prohibited, but no one enforces the ban; and I never encountered any problems, even though my luggage is x-rayed at every border.

The old houses are brightly colored, or still gleam with their original wooden furniture. Locals and craftspeople have lanterns hanging over the street, where candles are lit at night. We disperse, and I discover a small, hidden shop with a small sign advertising names translated into Chinese. I enter the room, but there’s no one around. I look around, then an unfriendly elderly woman asks me what I want. I point to the sign, then she disappears into the back of the house. From there, a small, skinny old Chinese man approaches and gives me a friendly welcome.

I tell him again that the advertisement lured me in. He nods, waves me into a smaller adjoining room, and asks me to sit at a table opposite him.

He introduces himself and pulls out his notepad to write down my name. He writes it phonetically into Chinese. But I want the name translated, which takes a really long time to explain to him. Glad to have understood what I want, he gets to work. “Alexander,” translated from Greek into English as “protector,” is “Bao Hu Yen” in Chinese. He asks me what kind of paper I’d like the name written on, and I choose one. With fresh ink, which his wife brings just then, and a brush that he spends a long time selecting from a large stash, he draws my name on the paper. He stamps the note with his house stamp and signs it, the local method of verification (and, of course, brand advertising). At my request, he writes the Vietnamese translation, “Njyu Bao Ho,” on the back. The whole thing costs me 20,000 dong, about one and a half euros. We bid each other a very warm farewell, the old man extends his bony hand to me and wishes me all the best.

Hoi An is a truly enchanting city

Of course, none of my friends are on the street anymore. I wander for a few hours through the small, paradisiacal Hoi An, passing small artisan shops and crossing what seems to be the famous Monkey Bridge (Chùa Cầu), a covered Japanese bridge made entirely of wood, with monkey statues at each end. What seems quite absurd to me is that some craft shops, like museums, require special admission coupons. You have to buy a set of coupons if you want to visit museums, some temples, and old artisan and aristocratic houses, for example. And apparently, you have to buy a set of coupons for the bridge too, but even after crossing it three times, no one speaks to me there, unlike at all the other buildings, where people ask for my ticket after I step over the threshold for the first time.

From the street you can look into some pottery workshops, and picture galleries line the alleys.

Only the cyclo and motorcyclists are annoying with their constant questions and you have to assure them every time that you are just taking a walk, unless you completely ignore them.

At some point, I meet Jane again, who’s browsing through some shops. She was also looking for the Monkey Bridge, which I can lead her to again. On our way, we meet Nicki and a number of other attentive cyclo riders. At a school, there’s a big spectacle going on, which looks like a large dance of Boy Scouts, led by a senior Boy Scout in the center. After watching for a while, we decide to rest and freshen up a bit, and meet for dinner at the restaurant we’ve been to at lunchtime. The “Mermaid” is delightful, the staff friendly, and the food excellent.

Only at sunset does the true beauty of Hoi An reveal itself

As the sun sets, the streets suddenly come alive. We throw ourselves into the hustle and bustle. I ask people why they’re celebrating, and they explain that today is a full moon, and that it’s always a celebration in honor of families. And in passing, people grin and assure me that I’m really tall. There are mostly young people out and about, and I joke around with them. Several girls approach me or have their friends approach me.

On the Thu Bon River, people float candles in small, colorful lanterns; boats float on the water, with glowing fish and dragons emerging from it; stages are set up along the banks where magical plays are performed. Another bridge has been built across the other bank, floating on the water.

A few officers are directing traffic across, only a few hundred people in one direction at a time to prevent chaos. There is a huge rush for the bridge, but I see no reason that justifies the popularity of the other bank. Kevin, Jane, Becks, Mia, and Brian are walking with me. We lost Glen, Euen, and Nicki somewhere in the crush around the bridge. And all the time I see people, young and old, grinning when they see me. Then I greet them, and they are embarrassed, because their decorum forbids comments like that. But since I don’t appear angry, they are friendly, and we have funny conversations, although hardly anyone speaks English.

Every now and then, I see Kevin with freshly opened beer bottles. We walk along the quay through the hustle and bustle to another bridge, which is hardly used. This brings us to the other side and allows us to explore what’s here. But there aren’t that many people here. The ground is sandy, and stilt houses stand scattered among the palm trees. Kevin finds another stand where he gets a new bottle of beer.

We now walk back along this side of the quay, the path somewhat illuminated by torches, lamps, and the full moon. At the end, where the floating bridge lands on this bank, I see a lively circle. A system has been set up in the middle of the crowd; people with microphones are speaking and singing. One person is asking questions, handing out small flags, and then handing out signs. Some of the remaining flags are hung on a line above the people. I don’t understand the system, and it doesn’t seem particularly exciting, so I walk across the floating bridge, which is now relatively empty and seems open to our direction, to the other side. I go for another beer with Kevin and the girls. After we’ve talked a lot, and the girls have finished another fruit salad, Kevin suddenly leaves the table after his second beer, walks up to a motorcyclist, and asks him:

“Are you taxi driver?” – “No” – „Can you drive me to my hotel?” – “Ok” And he was gone. But the streets were suddenly deserted, unlike before. It was 10:00 p.m., the middle of the night for a small Asian town. We walked a bit longer and found a restaurant where we sat on the street and leisurely ate dessert. I ate another tiramisu, but it wasn’t nearly as good as the one in Hanoi. Afterward, we slowly made our way back.

The next morning, I arrange to meet Brian after lunch at the beach. One by one, everyone joins us until we all decide to meet at the beach. I decide to stroll around Hoi An a bit longer, and Jane and Glen come with me. First, we go to a couple of tailors where they both have orders. The shops are truly delightful; the seamstresses offer everything they normally sell in the way of shirts and trousers, in all fabrics and colors. They have a wide selection of fabrics from which you can choose your favorite. They also have several Western catalogs, Peter Hahn, C&A, from which you can pick out the items you’d like. The seamstress takes your measurements, and the next day you can expect to have your jacket, trousers, shirt, blouse, or more. For five to twenty dollars.

While Jane is trying on clothes, I buy myself a one-and-a-half-liter bottle of water for thirty cents. While Glen is trying on clothes, I chat with a Vietnamese man sitting outside the tailor’s shop, watching the tourists. He’s delighted to hear I’m German. Because, he says, it was a German doctor who saved his life almost thirty years ago when he was hit by a grenade. He was in the South Vietnamese army, fighting alongside the Americans against the North. As I say goodbye, he gives me his blessing for life.

Jane, Glen, and I decide to see a few more of the famous ancient houses and temples and buy a ticket for five “attractions.” Of course, it’s free for locals.

First, we visit a Chinese assembly hall. The hall is surrounded by a beautiful rock garden, and orchids adorn the entrance gate. Inside the hall itself, there’s a pond and several shrines, as well as, as everywhere, sand jars for burning incense sticks. Small ornamental trees stand in the corners.

Next we stroll to a museum of the revolution.

The house is also very old, exhibiting finds from ancient and medieval times and chronicles of the deeds of the revolutionaries during the French colonial period.

We also visit the house of an old mandarin who once lived here and receive an exclusive tour through the old building. Our little guide tells us about the mandarin’s time, the architecture with its Vietnamese, Japanese, and Chinese influences, the life of a nobleman and his family, and, of course, she also offers us a few souvenirs.

Finally, we take a guided tour of an old craftsman’s house. The houses resemble German half-timbered houses. We’re here at lunchtime, and all the craftsmen are sleeping on the spot next to their current projects. This doesn’t bother the guide in the slightest. It’s remarkable that, unlike the guides in our museums, everyone here speaks very quietly. You have to listen very carefully to the whispers to learn anything about the objects. Furthermore, the guides are always young, attractive women dressed in traditional skirts or “uniforms.”

Hoi An is considered a handicraft and art town

Check out more of my juvenile trip through Indochina!

In the craft shop, the most intricate wooden figures are carved, including entire sailing ships with rigging. Silk fabrics are woven, and beautiful pictures are painted and sewn.

After eating, I’m about to look for a bike, which I can rent anywhere, that would take me to the beach. Suddenly, Euen and Kevin, with Becky and Mia on the back of their motorbikes, come whizzing around the corner and offer to give us all a ride to the beach on their scooters. We don’t say no, and in four laps, we’re all at the beach, even the Canadians. But after a quick lap, they’re already leaving the beach again. Their obvious fear of water is strange, because they miss every opportunity to swim on their entire trip.

The soft sandy beach seems endless, bordered by palm trees, and there aren’t many people here. Children frolic in the water.

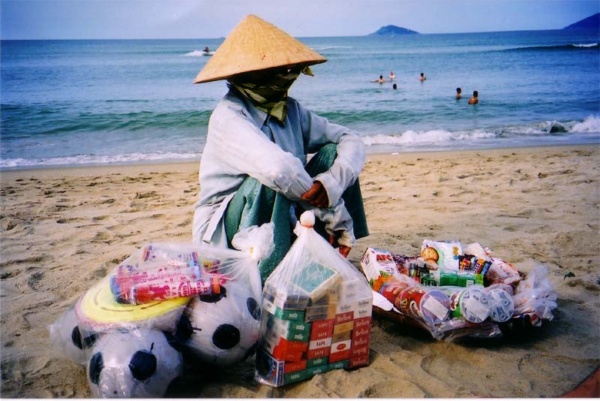

I haven’t even put my things down yet when I’m already besieged by two veiled vendors offering me fruit, water, cigarettes, and soccer balls. Annoyed, I give them the runaround; I want to go swimming first. Of course, we always leave one of us on the beach to guard our things, but we take turns quite often.

The waves aren’t exactly high, but they’re still enough to give you a good head wash. Kevin and Glen toss the kids in the air. I swim out a bit with you, because we notice that most of the waves break before reaching the beach. About a hundred meters further on, we can stand again and let the waves crash over us.

On land, Jane and I watch the activity in the sea and see Becky and Glen speeding off into the distance on a jet ski. After much persuasion from Loli, one of the vendors, I finally allow myself a peeled pineapple and a few cookies. Another vendor named Lavli promptly joins us and tries to persuade me to buy another pineapple. The conversations get more and more bizarre; I try to get her to attack the people who haven’t had a pineapple yet. But the nice vendor naturally has a lot of arguments: she goes to school and needs the money, no one has bought anything today, and anyway, she only wants to sell it to me, otherwise she won’t talk to me anymore.

But it’s no use, I’ve had enough pineapple, and Lavli leaves me sulking.

We return to the city on our motorcycles. Euen is at a breathtaking speed, speeding past other scooters and trucks. I tell him he should at least honk like the Vietnamese and pay them back. By the way: scooters are cheap to rent; the standard price is four dollars. Helmets aren’t included as standard equipment.

The next morning we leave the hotel again and head to Da Nang, where we take a small plane to Saigon.