Diary Entry

The small, ancient royal city of Hue is very impressive. But we haven’t seen much of Vietnam itself yet. Now it’s time for that; we’re going on a trip! Our motorbikes are waiting for us early in the morning. We won’t drive ourselves; everyone will have a driver. Dan introduces himself to me. First, we’ll speed to the Perfume River to take a dragon boat ride up the river to the tomb of King Minh Mang (Hiếu Lăng – lăng mộ Hoàng đế Minh Mạng).

The dragon boat is once again a family houseboat, a kind of large catamaran, with the floats carved and painted into dragon heads on the ends. During the trip, family members treat us to their wares, the usual paintings and fabrics. We can’t run away from here.

Only a few sand boats and fishermen occasionally fish in small boats near the shore on the river. On one side, there are sweeping views of rice and peanut fields and banana plantations, while on the other, mountains and forests stretch out. We stop on the mountainous side and, after a short climb, meet up with our motorcycles again. Our guide accompanies us and explains a bit about Vietnamese life and teaches me new words.

The route leads through a few villages and through the forest at a dizzying speed. The drivers are afraid to take us across a very fragile suspension bridge, so we have to walk across it one by one. Then the rapid ride continues. As we pass people, they wave. Children, in particular, enjoy high-fiving us when we hold out our hands.

People lay their rice out to dry on the road because there’s no other better area available. We pass through columns of smoke from rice grass being burned for fertilization in the fields, or in our case, at the edges of them. Some of our paths lead right through the thick forest, so branches and leaves whip at my face if I don’t duck my head quickly enough.

On the way, we also make a short stop in a village where incense sticks are made. This involves making a paste of incense from many ingredients and then wrapping it around sticks. We’re invited to try it ourselves, but the women have such a wonderful technique, with which they can twist a stick in seconds, that we’re nowhere near able to match it.

We finally reach the entrance to the king’s tomb. It’s more like a park, except that souvenir vendors have already set up shop in front of it. The innermost buildings are surrounded by a kind of moat, in which lotus leaves and blossoms float. On small islands, there are tiny pagodas and covered terraces dating back to the time of construction. The king was aware of the beauty of the place. And he loved pine trees, so he had them planted all around. I walk through an avenue of pine trees, pass through two gates, and past a guard of stone soldiers, who were admittedly very small, for the king himself was a tiny man and did not tolerate anyone taller than himself.

At least not in his guard, alive or dead. I follow the path through some walls until I reach the sarcophagus, protected by a rampart but exposed to the sky. There are inscriptions all over the walls. We can see the pine trees towering around us. In front of the small entrance leading to the sarcophagus stands a small tower, on which a stone slab inscribed with ancient Vietnamese characters tells the story of the king. He had 129 concubines, yet he remained childless, even though his only wish was to have a successor.

The journey continues past villages, stopping briefly in one to watch a woman rolling incense sticks after making the necessary incense paste. At another point, we stop briefly to climb an old American bunker, from which we have a magnificent view over the Perfume River valley. There’s no sign of a town; nature reflects in the valley, which is surrounded by a mountain range.

There are bushes and wild orchids growing around us.

Our next stop, after climbing a rocky mountain landscape on our motorcycles, is a beautiful monastery. Our drivers park their bikes in the small alley leading to the monastery. I see the monks walking into the back of the monastery after a prayer.

From the outside, the monastery looks more like a farm, lacking a pagoda or Buddhas, and chickens roaming around in the courtyard. On the ridge of the roof, I see a nest of bees or wasps; it’s hard to say for sure, as these insects are almost the size of hornets and, apart from a yellow stripe, almost entirely brown. We can eat here, and after we take off our shoes, a nun leads us into a room inside the monastery. From here, you can see the small courtyard, which resembles a miniature Garden of Eden. There are small trees and orchids, ferns, and a small fountain. The nun invites us to wander around the monastery after dinner and, if we like, to take a nap. In return, she offers us the use of the prayer room. Then she leaves us.

As soon as we sit down at the table, two young novices bring food. The food is entirely vegetarian, but by far the best vegetarian meal I’ve ever eaten. There’s an abundance of snacks like spring rolls, little chili cookies, mysterious banana leaf pies, prawn crackers, lemongrass vegetables and beans, and of course, as much rice as we can manage, vegetable balls, and noodles.

As soon as our glasses are even close to empty, a girl discreetly and gently, like a fairy, comes over and refills them. The approximately eight-year-old, dressed in a typical novice’s habit, is always confused but naturally delighted when I thank her.

Half of us immediately head out to find a quiet spot after dinner, but miss out on the amazing dessert. There are fruits: bright red lychees covered in hairs like anemones, and dragon fruit that looks like red pineapples on the outside and kiwi on the inside. And to top it all off, there’s something called Yin & Yang, a small box wrapped in coconut leaves that opens when you remove a small wooden lock and unroll the leaf. What appears to be a white, sticky mass inside a second coconut leaf that you can touch. This dessert is, firstly, an ingenious design, and secondly, it tastes excellent. The white mass consists of desiccated coconut and refried beans. It gets its name from this duality, outside and inside, and this ingenious “nesting” of the two.

We take our time in the monastery and have fun with the young novices. Another girl joins the boy and girl, but she looks only five or six years old. In the room is a blackboard on which are written English sentences with blanks and verbs in parentheses, obviously homework. We help the girl with her homework and ask her to write our names. In return, she writes her name and those of her friends in Vietnamese characters. Her name is La, the boy’s name is Bi Sop (which inevitably gives us the funny similarity to the English word “bishop”). In Vietnam, unlike all other Asian countries, Latin script is used for writing, which was introduced here by the French. But in monasteries, people remain true to the old tradition.

For fun, I put my cowboy hat on Bi Sop. He’s thrilled, and the little monk with the hat on his head is a picture for the gods. He asks if it’s a gift, but unfortunately, I still need the hat.

We’ll have to say goodbye again soon. The little ones wave goodbye to us for a long time. The sad thing about trips like this is always having to leave such dear people so quickly. It’s a sad experience that I have to deal with again and again throughout the entire trip.

The tour continues, the drivers speeding down the mountain and through the bush. We stop at an ancient ruin. According to our guide, it’s the only colosseum in all of Asia where tigers and elephants once fought for their lives. Now it’s overgrown with moss and vines.

As we gaze at the old arena, village children frolic around us. They climb boisterously all over Kevin and me, and one little boy, in his eagerness, rips the ribbon off my hat. Luckily, I’m able to sew it back on with a needle and thread.

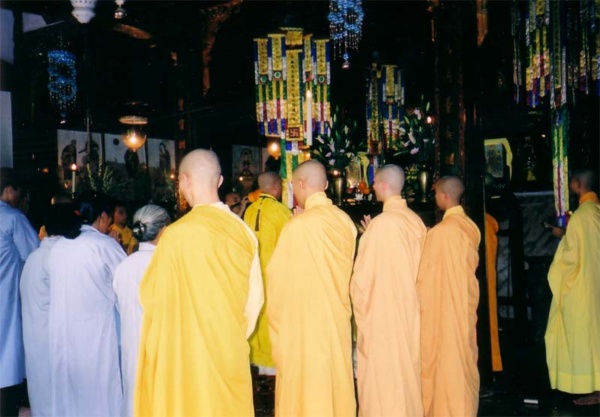

We stop in another forest, near a pagoda. Inside the monastery, the monks are preparing a service. I take off my shoes and crawl into the temple room; only monks are allowed to walk here.

The nuns gather in front of the entrance, dressed in white as usual. But unlike nuns in other Buddhist Asian countries, they don’t seem to need to shave their heads.

The monks gather around the Buddha statue and the altar. A chosen monk reads from scriptures in a sort of chant. Once he has finished, the abbot steps forward; unlike the monks in orange robes, he wears yellow. He is also the oldest. He kneels before the Buddha and chants, with the monks responding regularly.

Monks leave the room every now and then, but return after a while. One monk stops to ask me my name and where I come from. He nods at me in a friendly manner, murmurs blessings, and turns away again.

Finally, I leave the prayer room and explore the monastery. There’s no sign of my companions. Everywhere, I see novices sitting alone in a corner poring over books, or others sweeping around the houses. The monastery is a larger complex that stretches across the forest. Individual covered corridors connect living quarters, temples, dining rooms, gardens, and study rooms. But I also see a volleyball court. I repeatedly encounter young monks who greet me.

At some point, I meet my companions again, and we continue on. The roads are so dusty that the reddish dirt covers us from head to toe. We leave the forest again and speed through villages where people are once again spreading their rice on the streets, threshing rice, picking bananas from the trees, and waving to us.

We pass a long road across a plain of rice fields, and we often have to walk past the farmers’ carts, as they block the way. Small bamboo bridges cross the canals and the small rivers that flow through the countryside and the villages. They’re essentially just bamboo poles laid over the stream, canal, or river. If you’re lucky, they’ll even attach a second pole slightly higher up to act as a railing. But for heavily laden farmers, such a thing would only be a hindrance. I try my luck crossing one of these bridges, and even without luggage, it’s a difficult balancing act, but I manage to survive it dry.

This is how I imagined romantic Southeast Asia

We continue on, but then a sight presents itself that compels us to stop. Further down the river, we see a shepherd of a very special kind.

On a boat, the Vietnamese man drives a large quacking carpet, a huge flock of about a thousand ducks, in front of him.

Check out more of my juvenile trip through Indochina!

In the afternoon, we stop in a village to give the motorcycles a little rest. It’s just a small village of rice farmers. There’s even a beautiful Japanese bridge over the stream, and swarms of dragonflies fly through the air. Villagers offer us chairs. I first walk around the village a bit.

It’s quiet; most people are still in the fields. Water buffalo graze in the meadows. Children play on the paths. Finally, I sit down with Nicki, Glen, and Nicky and drink a strong Vietnamese coffee.

When we get back to Hue, the drivers can’t resist speeding through the bustling market, honking wildly.

The girl who’s been shaving a few people the day before almost drops her comb as we whizz past her salon and wave to her. Then she waves back wildly.

At the end of the day, I dine with Glen, Euen, Jenna and Brian in the hotel park under a starry sky.

Tomorrow I’ll head over the mountains to the sea. There, the beautiful little town of Hoi An awaits me.